ZOOM image HERE.

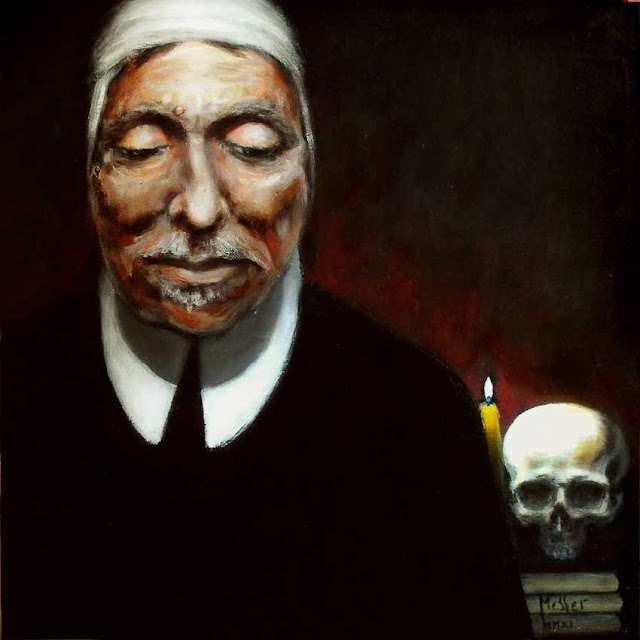

Doing the portrait of a historical figure such as Oliver Cromwell requires having a sense of History.

This painting was submitted to Huntington's Cromwell's museum.

Doing the portrait of a historical figure such as Oliver Cromwell requires having a sense of History.

This painting was submitted to Huntington's Cromwell's museum.

Who was Oliver Cromwell?

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 1599 – 3 September 1658 ) was an English military and political revolutionary leader best known in England England

His rise to power was a consequence of the English Civil War (1642–1651), a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians (Roundheads) and Royalists (Cavaliers), partisans of King Charles I (1600 –1649).

After the first Civil War ended, Cromwell tried to negotiate a “limited monarchy” but Charles’s intrigue with the Scots and perfidy led to a second Civil War (1648–1649) which he lost. He was tried and beheaded. His son was exiled and English monarchy was replaced with first, the Commonwealth of England

Controversy around Cromwell’s legacy: his head

When Charles’ I’s son, Charles II returned in 1660 to restore the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies, he demanded that Oliver Cromwell's body be exhumed, along with those of two others implicated in the execution of his father. The bodies were removed from Westminster Abbey on 26th January 1661 , to be tried and found guilty of high treason as revenge against Cromwell’s treatment of Charles’s father.

Four days later, on the anniversary of the execution of Charles I they were dragged to Tyburn. After a macabre hanging from the gallows all day before being taken down and having the heads severed from the bodies. It took more than one blow to remove Cromwell's head. Their heads were placed on poles on Westminster Hall as a warning to others. Another Cromwell ‘s death mask was then made and copies sent to every town and city that had been most loyal to the monarchy.

Cromwell‘s embalmed head was so displayed for 25 years.

At some point soon after 1684 the head either fell or was taken down. There is a strong tradition that it was blown off in a gale, retrieved by a sentinel, and hidden for many years. There is some evidence that it was in a private museum in London

It seems his head was later sold many times until it came into the possession of the Wilkinson family from the nineteenth into the twentieth centuries. Canon Horace Wilkinson, agreed in the early 1930's to allow two scientists full access to the head. Their conclusion was that the head was that of Oliver Cromwell (Pearson and Morant study).

Following Canon Wilkinson’s death, a suitable home was sought for the head.

It was again offered to Sidney Sussex College

Controversy behind Cromwell’s first image: his wax death mask

|

| Cromwell’s wax death mask |

Cromwell’s “wax” death mask is probably the best-known death mask of English history.

It was originally owned by Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) whose collection contributed to the founding of the British Museum

When Cromwell died, his actual body was initially secretly interred in Westminster Abbey. But unknown then to those coming to mourn and before it began to putrefy, a wooden effigy of Cromwell with a wax mask that lay in state at Somerset House. The funeral effigy depicted Cromwell as a King, a title which he had refused in his lifetime.

The “wax” death mask of Oliver Cromwell was taken after the embalmment of his body and it shows the cloth bound around his head to cover the cincture.

I decided to keep it instead of a traditional puritan hat or helmet, adding I believe more modesty to his memory. This way also reminds me of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)‘s self-portrait as “St Paul”.

|

| Rembrandt van Rijn ‘s self-portrait as “St Paul”. |

Death masks were widely distributed through private and public collections and were also used as models for posthumous portraits. By using his to realize his portrait, I decided to keep this old tradition alive... as his opening eyes witness this.

“Warts and all”… a Dutch “Vanity”

Commissioning a portrait was at the time as still is, intended to flatter the sitter. Cromwell was well-known for being opposed to all forms of personal vanity.

The first record of that famous “Warts and all” phrase as being attributed to Cromwell’s comes from Horace Walpole's Anecdotes of Painting in England (1764). It is said to derive from Oliver Cromwell's instructions to his painter Sir Peter Lely, and was reported in a conversation between John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham, and the house's architect, Captain William Winde. Winde claimed Cromwell saying that:

"Mr Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint my picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughnesses, pimples, warts and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it."

Following his posthumous instructions, I decided to paint his portrait as truthfully to his real appearance, not based on his portraitures. I therefore decided to paint him after his death mask, i.e. his most faithful image. His last image too.

I chose to do his portrait in manner of a Ducth Vanitas painting.

Vanitas is a type of still-life that became popular in Europe , particularly in the Netherlands

|

| Vanitas by Pieter Claesz (1772) |

The term “vanitas” comes from the Latin word meaning “emptiness”. The primary themes were impermanence, mortality, the meaninglessness of earthly life and delights when compared to the everlasting nature of faith. The idea comes from the Bible: "Vanity of Vanities, saith the preacher, all is vanity” (Ecclesiastes 12:8). Vanitas often have a human skull and a candle as a direct reference to man’s temporary existence on Earth.

I also thought that a 17th C Dutch style would be more appropriate than say Flemish Baroque painter Anthony Van Dyck’s (1599 –1641) who is most famous for his portraits of Cromwell’s enemy; King Charles I, his family and court.

Van Dyck was one of the most influential 17th-century painters in England

But Van Dyck was born in the Southern Netherlands , a region recaptured from the Dutch Republic Spain Belgium

To highlight the Dutch influence over Cromwell, I decided to paint him in the style of this Dutch contemporary painter Rembrandt van Rijn.

As an artist I am deeply influenced by his “light and shade” technique and painted using his style/technique for many years. Rembrandt was never about flattering his subjects and used to paint rough with thick paint.

Cromwell’s Dutch card?

When William II, Prince of Orange and head of the Dutch Republic Dutch Republic Spain

Cromwell’s hopes may have also been supported by the contribution some Dutch did to the draining of the “

Cromwell’s hopes may have also been supported by the contribution some Dutch did to the draining of the “

To this purpose, Cromwell sent in 1651 Oliver St The Hague Holland England Dutch Republic

However, Cromwell had another card up his sleeve; he also wanted to attract the rich Jews of Amsterdam to London Spain Holland England Amsterdam London England

My Cromwell portrait is a kind of posthumous gratitude from the Jew I am.

Sources:

My Cromwell portrait is a kind of posthumous gratitude from the Jew I am.

Sources:

- Cromwell's Head and its Curious History (Facebook)

- Oliver Cromwell's death mask for sale

- Wax death mask of Oliver Cromwell

- The last words of Oliver Cromwell

- Oliver Cromwell (Wikipedia)